Exemplarism in Classical Metaphysics

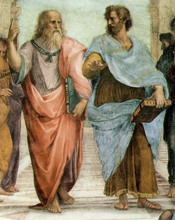

Tired of the traditional discursive arguments for or against divine existence? Walk in the footsteps of great thinkers such as Plato, Plotinus, and Augustine, and consider ‘exemplarism‘ in classical metaphysics, an ancient methodology in metaphysics which eschews syllogistic ‘proofs’ in favor of a methodology of direct apprehension with the mind of universal givens.

Modern movements of skepticism, such as atheism and agnosticism, conceive of the question of divine existence as being either unintelligible or, at the very least, unknowable with the mind. On the other hand, within the church and among several world religions, arguments for divine existence have usually utilized deductive or inductive syllogisms as ‘proofs.’ Unfortunately, such proofs are arguably either probabilistic in nature or commit the Fallacy of Composition, affording the believer with little in the way of knowing with the mind whether the truth-claims of his or her faith can be verified.

However, metaphysical exemplarism is methodologically distinct from discursive arguments. It also has an ancient tradition which has been neglected and sometimes suppressed in modern times, whether in sacred or secular contexts. This tradition is rooted in the thought of Plato, Plotinus, Augustine, and others, and it asserts that divine existence is ‘epistemic’ (knowledge-based), rather than ‘doxastic’ (probabilistic), as intelligible universal givens are apprehended directly with the mind. This is exciting news for skeptics and believers alike who may be troubled by an ostensible ”knowledge gap” in regard to divine existence.

The so-called “traditional” arguments for divine existence are discursive (syllogistic) in nature, and were first articulated by Aristotle but later polished by Thomas Aquinas and others. Although much effort and scholarship have been expended upon these arguments by ardent and intelligent spokesmen, they suffer primarily from the weaknesses found in inductive and deductive logic.

Inductive arguments proceed from finite particulars of information and attempt to achieve a universal conclusion. The form of inductive argument would appear as follows:

1. John is a mortal human being.

2. Susan is a mortal human being.

3. Every other person I have met is a mortal human being.

4. Therefore, all human beings are mortal.

The reader will note that the problem with this syllogism is that one is limited by not being able to meet every single human being. Therefore, the conclusion, which claims universality in knowledge of human beings, cannot be made with certainty. Only probability is possible in inductive logic, so the conclusion should be more accurately written,

4. Therefore, all human beings (probably) are mortal.

Deductive syllogisms have as their first premise a universal proposition of some kind. If its form and validity are maintained, deductive syllogisms yield certain conclusions, because they argue from a universal premise to a particular, finite conclusion. The following sylogism is an example:

1. All human beings are mortal.

2. Socrates is a human being.

3. Therefore, Socrates is a mortal human being.

As the reader can see, because the set of humans in the first premise is larger than those in the second, then the conclusion is certain. However, the primary besetting weakness of deductive logic is how the first (universal) premise is apprehended — Is it apprehended by a prior induction? If so, then the conclusion can be only probable. If it is apprehended via a prior deductive premise, then a vicious infinite regress is set up. If it is apprehended by direct apprehension of universally given properties, then at least some divine existence is apprehended non-syllogistically, yet the argument does not articulated just how such an apprehension is possible.

In addition, the ‘traditional’ argments usually commit the “Fallacy of Composition,” because they structure their arguments as ‘analogical.’ The Fallacy of Composition is the faulty assumption that the whole will be like the parts in relevant ways. If structured analogically, the so-called “teleological argument” would take the following form:

1. Every ticking clock must first be made and then wound up by a person.

2 If I found a ticking clock in the forest, then there must have been another person who first constructed and wound up the clock.

3. The entire universe is like giant clock.

4. Therefore, there must have been a personal being who first made the universe and set it in motion.

The reader can detect the Fallacy of Composition in this argument, especially with the use of the word, “like,” in premise number 3. The problem, of course, with the argument is that, unless one has access to infinite knowledge, then it is impossible to know whether a part of the universe (the clock) is like the whole (the universe) is relevant ways. That is, one might ask whether the universe as a whole might be essentially non-personal, like a force, yet with creative properties.

(to be continued)